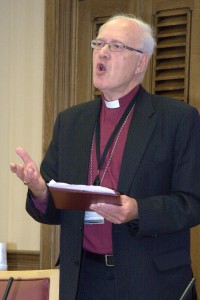

Raising the issue of worldwide persecution of Christians, a CBC House of Lords Symposium took place on 25th February under the banner 'Persecution: Our Response?'. One of the main speakers was the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord Carey of Clifton. Here is his very well received address which we publish with permission.

I am delighted to be here for the Annual meeting and want to thank Olave Snelling for inviting me. I also want to thank the Council for the way it promotes such fearless Christian work in this country. Today also allows me to express my admiration for Baroness Cox and her remarkable work throughout the world. She is an inspiration to so many.

The focus of our gathering is our concern that so many Christians throughout the world suffer for their faith. Indeed, the century we have left behind was conspicuous for the fact that there were more Christian martyrs in the 20th Century than at any time in the past. It is surely right, then, that we should do our utmost to identify with the suffering churches and share something of their pain and seek to intervene on their behalf.

I have just read an interesting book by the Swedish writer Henning Mankell called The Dogs of Riga. It was published in 1992 and is set in the cold war between the East and West. Wallander, Mankell's troubled policeman, is called to investigate the murder of two Latvians whose bodies are found on the Swedish coast. He is joined by a Latvian policeman called Major Liepa. Over a drink one evening, the Major says this: 'In your country I see an abundance of material things. It seems to be unlimited. But there's a difference between our countries that is also a similarity. Both are poor. You see, poverty has different faces. We lack the abundance that you have, and we don't have the freedom of choice. In your country I detect a kind of poverty which is that you do not need to fight for your survival. For me the struggle has a religious dimension and I would not want to exchange that for your abundance'.

This speech lingers in Wallander's mind for some time. Then he learns that the major on his return to Latvia is murdered and Wallander is sent to that Eastern European country to help find the major's murderer. He meets up with the major's widow, called Baiba, and is caught up in the Latvian freedom movement. Towards the end of the story there comes a moment of revelation when, with Baiba, he shelters from the enemy in a Church. 'The night they spent in the church became the point in Kurt Wallander's life when he felt that he had penetrated to the very centre of his own existence. He had never previously looked at his life from an existential point of view. It is possible that at moments of deep depression he might have been struck by the thought that life is so very short when death strikes. One lives for such a short time but will be dead forever. But he had become adept at brushing aside such thoughts.. the night he spent with Baiba Liepa in that freezing cold church made him look deeper into himself than he had ever done before'.

As I read the book it struck me how relevant it is to what we are discussing today. Major Liepa, from Latvia, considering the contrasting countries, dismissed freedom as providing a fundamental value that eclipsed other values. As a religious person he knew that freedom took many different forms and that, if one used it only for oneself, it is ultimately of limited value.

So it is with respect to our own country which prizes freedom to such an extent that, ironically, those who cherish faith and interpret freedom in its light are sometimes in danger of being deprived of it. Andrea Williams will dwell on this at greater length later and, right now, all I wish to argue is that Christianity, which has given so much to our country, and which continues to make an impressive contribution, is now being sidelined as never before, as though it is a stranger to our nation.

We should be careful however not to draw too many parallels between the experience of Christians in the UK and the plight of Christians abroad. As far as the UK is concerned Christians are rarely 'persecuted', and direct comparisons should be avoided. What is happening in Western Europe is not persecution but a marginalising of faith which seeks to portray it as a matter of personal conscience only. Some examples of this originate from a mistaken but well-meant political correctness that is anxious not to upset minority faiths by seeming to 'privilege' Christianity. Hence the regular 'pantomime' every Christmas where some local Council or another absurdly gives Christmas another name.

Of course, I not am denying for one moment that since 9/11 - and the date is significant - a new breed of atheists have moved into the public square arguing that Christianity, or any other faith, should have no role in public life. This strident and bullying campaign seeks to ban faith schools, in spite of the clear evidence that such schools perform better than many others. We have reached a point where politicians are now criticised and mocked for merely expressing their faith.

It is clear that we must stand up against the marginalising of faith. We must constantly remind society, of its Christian roots and heritage. Christianity has made a more positive contribution towards social capital than many realise. Church Schools, for example, were there before the State provided public education and even now educates a quarter of all children in the land. As I wrote recently, if we behave like doormats, don't be surprised if we are treated as though we are.

Let me now turn to the actual persecution of Christians abroad which I have sadly come across many times during visits throughout the Anglican Communion. During my time as Archbishop one of the greatest challenges was to remind political and religious leaders in lectures, meetings and discussions the need for a fair and equitable treatment of Christian minorities.

I am aware that the present Archbishop of Canterbury has done the same in his visits abroad. Nevertheless, in spite of such strong representations, the problem remains. And, wherever we look, particularly in the Moslem world, we find our Christian brothers and sisters treated as second class citizens, unable to build churches, unable to invite others freely to join them for worship and certainly not able to evangelise and baptise those who are attracted to the Christian faith.

This is not to say that other faith leaders are uncaring or unmindful of these concerns. I have spoken personally to significant Muslim leaders around the world and I have been impressed by their desire to help Christian people. I think of the many personal conversations I have had in the past with Dr.Tantawi, Grand Imam of Al-Azhar in Cairo. No one could more considerate than he in expressing his regret. In spite of such appeals, however, little has changed. In Pakistan the tiny Christian minority are vulnerable as churches are attacked and as the notorious Blasphemy Laws are imposed. In northern Nigeria clashes between Muslims and Christians are dismissed by the West as inter-community conflict without any real understanding of the way churches have been razed to the ground and Sharia law imposed on non-Muslim people. In Malaysia recently nine churches were attacked because some Muslims were outraged that Christians were allowed to use 'Allah' to address God. As far as Sudan is concerned, Baroness Cox from her rich experience knows very well the sorry tale of the way Christians are victimised and church property is seized by the Islamic government.

Allow me now to outline actions that we should take to represent fellow Christians who are deprived of freedom to practice their faith.

Praise the Lord for lord Carey`s speech.

I pray that many more Christians in Parliament will follow His lead.